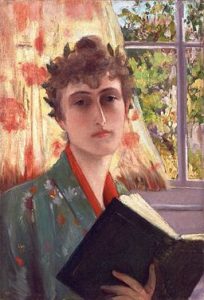

One hundred years ago, musicians didn’t have record labels — they had patrons. A patron was a single wealthy individual who made a hobby of supporting the artistic efforts of composers or other artists they liked who seemed promising to them. Such a one was the Princesse de Polignac, which sounds quite grand until you learn that she was born Winnaretta Singer in Yonkers, NY and only married into her title. As you may have guessed from her maiden name, she was heir to an enormous fortune which enabled her to further the careers of many young avant-garde musicians including Eric Satie, Igor Stravinsky, Maurice Ravel, Gabriel Faure, Francis Poulenc, Claude Debussy, and Kurt Weill, among others. I use their full names because in those days, they were still people and not just famous icons of the art world who have passed into the stuff of legend…

One hundred years ago, musicians didn’t have record labels — they had patrons. A patron was a single wealthy individual who made a hobby of supporting the artistic efforts of composers or other artists they liked who seemed promising to them. Such a one was the Princesse de Polignac, which sounds quite grand until you learn that she was born Winnaretta Singer in Yonkers, NY and only married into her title. As you may have guessed from her maiden name, she was heir to an enormous fortune which enabled her to further the careers of many young avant-garde musicians including Eric Satie, Igor Stravinsky, Maurice Ravel, Gabriel Faure, Francis Poulenc, Claude Debussy, and Kurt Weill, among others. I use their full names because in those days, they were still people and not just famous icons of the art world who have passed into the stuff of legend…

The Princesse de Polignac presided over her famous salon from the 1890s into the 1920s Artists and intellectuals used to gather, along with various aristocrats and other future luminaries such as Marcel Proust, in the de Polignac’s music room, which was large enough to hold a chamber orchestra, singers, and audience whenever the de Polignacs held a private performance. Anyone who was anyone went to these things and by programming the music of her favorites, the Princesse was able to promote their careers before the very people most likely to support them going forward. Apparently, it worked. Almost all of her protegees went on to lasting fame.

I would not know any of this had I not stumbled across a CD entitled From The Salon of the Princesse de Polignac, which intrigued me because I’ve been reading Proust and it occurred to me that salons of princesses are a rather Proustian thing. In fact, it is both the music and its milieu that make this collection interesting.

The disc contains three chamber operas commissioned by the Princesse for performance in her home, and recorded by a British group called the MATRIX ensemble twenty five years ago. Stravinsky’s Renard is the drawing card to get us to buy the disc, but there are two other equally interesting pieces from less renowned composers, Manuel de Falla and Darius Milhaud. Listening to all three together, one gets a different perspective on Stravinsky’s uniqueness as a composer. It’s not that Stravinsky wasn’t great — although he never got his picture on bubble gum cards. Nevertheless, he remains by far the best known of the early 20th century’s avant garde, with the possible exception of Ravel.

But when you hear de Falla’s El Retablo de Maese Pedro, you realize that certain elements of Stravinsky’s style — the orientalism, the occasional off key horn line, the driving syncopation, to name a few — are not unique to him. De Falla does it too. Even Milhaud shares a bit of Stravinsky’s allure. It’s a reminder that while Stravinsky is the biggest fish in the pond and the one we remember, he was not composing in a vacuum. Far from it, he was in Paris at a time of great cultural change and part of a circle of artists and composers who all knew each other. It’s to be expected that he was both driven by and a driver of that wave of change.

The Princesse was, arguably, an even bigger driver of change, using her abundant supply of cash to see to it that composers worthy of note got the support they needed to continue. Some of them didn’t need her money — Stravinsky and Milhaud in particular — but none of them turned it down. It was more the status and the access to a high end audience that drew them in. Without a product to sell other than the composition of the work itself, composers needed patrons and their commissions to keep them afloat.

In addition to commissioning musical works, de Polignac also supported the Paris Opera and symphony orchestra as well as the Ballet Russe. She commissioned ballets from Diaghilev and supported the writer Colette. Proust didn’t need her money — he was filthy rich himself — but he attended her salons from 1895 on and valued the friendships of both the Polignacs. Reading a list of the many artists they supported makes you wonder what early 20th century music and the arts in general would have been like without them and their taste for modern styles.

Today, self-promotion is the rule but only until you get someone with money (usually a large corporation) to notice you. Viewed in that light, the difference between having a record deal and having a patron is perhaps not so great, but one could also argue that the patronage system affords the artist greater freedom to do work that’s more than just appealing to a large number of people, i.e., the most profitable. Having no shareholders to report to, the Princesse de Polignac could afford to take chances, and as a result, an entire generation of innovative art came to light and flourished.

For more of the back story to the marriage of Winnaretta Singer and Prince Edmond de Polignac and their role in the Parisian art world, see the Parisian Music Salon website.